Why 2020 is So Hard on Your Mental Health

(Note: this is a short version of a much longer article I posted here on Medium).

The year started with massive fires in Australia, which started shortly after that time the Amazon was on fire. Then there was COVID-19, and I don’t think you need me to tell you the rest of the story.

2020 has been one wild rollercoaster, and I think it’s safe to say that very few of us are unscathed - and hey, we’re only 2/3 of the way through.

I don’t know about you, but… it’s getting harder to focus. I set goals, but then I don’t really feel like achieving them. I get distracted easily, sinking time into scrolling through my news feeds instead of sticking to what I’d planned to do. I’ve allowed myself far more junk food than I normally would, because I’m not able to relax with friends in the ways I’d normally like to. Many people have told me that they’re feeling the same.

And yes, I’m admitting this as a coach, because I too am human…

Long-term Stress and the Brain

One explanation for the effects of recent event on our brains is a simple one - we’re not wired to deal with long-term threats. We evolved to deal with simple, short-term threats - a lion that we have to run away from or an enemy that we need to fight - not an ongoing, slow-burning background threat that we can’t really see or figure out.

It’s not really what you want to hear when you’re already feeling stressed, but - long-term exposure to stress can damage us physically and psychologically. Prolonged levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) are linked with mood disorders, as well as motivation and mental agility. In other words, if you’re finding it harder to control your moods, to focus and to think clearly, then it could be because of the constant, background stress of the situation.

“If things haven’t changed that dramatically for you and you’re still financially stable, you may resist this — thinking “but how can I be stressed? It’s not like I’m out there on the front lines!” — feeling guilty for feeling bad when there are people suffering far more than you are.

I get this. But no matter how much we compare ourselves to others, it turns out that even small life changes can trigger a stress response: according to the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory, it is not just major life events such as losing a loved on or being fired that can cause a stress reaction, but things you wouldn’t expect such as marriage, vacation, a change in social activity, or changes to working hours.

Lockdown and the Brain

It’s not just the stress of knowing that a global pandemic is going on, of course — many people have been stuck at home with little to no human contact for months.

What’s the effect of that? Studies on mice suggest that social isolation can lead to obsessive or addictive behaviour, as well as increased anxiety and depression. Other studies have shown that social isolation is generally connected to higher risk of cognitive decline and dementia, and on the other side, it is generally accepted that one of the strongest predictors of wellbeing is strong social connections.

The effects of isolation during lockdown can of course be mediated by making time for regular video calls with your friends — but for people living alone, that doesn’t quite cut it. “Touch starvation”, or the lack of physical contact, has also been found to increase stress, anxiety and depression, and difficulty sleeping. The good news? Even hugging yourself, stroking your arm or self-massage can help somewhat.

On top of that, it’s not necessarily just isolation that can impact us — there’s a ton of research showing the benefits of spending time outside in nature (this is what I focused on for my MSc), and the negative impacts of “nature deficit disorder” on our health and behaviour. This is usually coupled with too much screen time and not enough exercise, and I’m sure you can guess the results of these by now: a lack of exercise can lead to depression and anxiety, while too much screen time can lead to depression, impaired cognitive function, and changes to brain structures involving decision making, attention and emotional control.

In other words, if we’re not spending enough time outdoors or exercising, it’s going to spell trouble for our mental health.

But is that all there is to it?

For many of us, our sense of meaning comes from setting and achieving goals, or of having a meaningful narrative that frames our lives in terms that make sense to us. Whether you recognise it or not, you have stories about who you are, where you came from, and where you’re going.

But when something like COVID comes along and tears up the foundations of everything that makes sense, it can leave you feeling raw, confused, and lacking a sense of meaning.

In the first episode of the webinar series I started hosing, appropriately titled WTF Is Going On? Finding Meaning in Our Chaotic World, I interviewed my friend Yannick Jacob, who is — among many other things — an existential coach (see the interview here).

We discussed how suddenly realising your own mortality can provide a stronger sense of meaning (after all, knowing that life ends can make every moment all the more precious), but at the same time this can highlight just how meaningless a lot of our day-to-day activities are.

One of our guests told us that the events of 2020 had made him realise how meaningless his job was.

I am putting together a series of webinars connected to the topics of sense-making, meaning, resilience, existentialism and deep adaptation, perhaps as a way to help my own brain make its way out of the fog and to make sense of the world we find ourselves in: check my events page to find out more!

WANT TO WORK WITH ME?

I’m currently accepting new one-to-one clients who want to:

Find clarity on their soul’s calling

Build a business, organisation or project to benefit the world

Shift their mindset and step into their true power

Develop more confidence and self-love

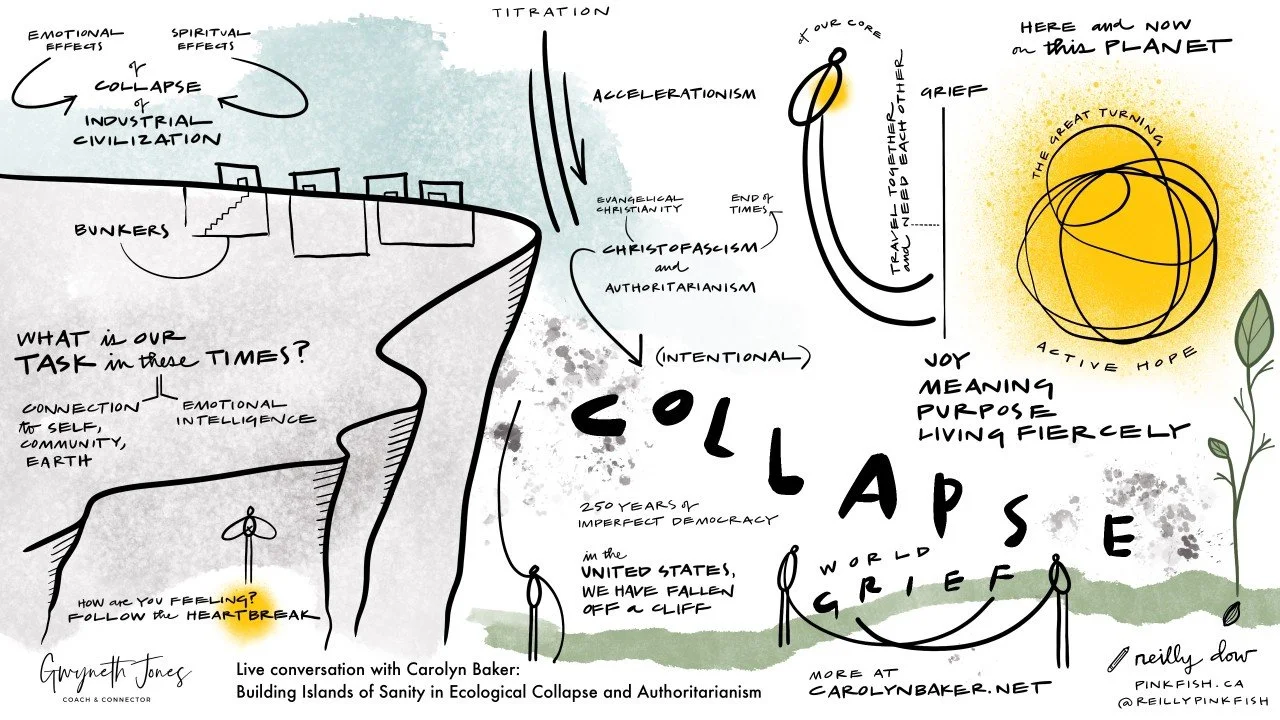

Prepare emotionally and practically for the collapse of our current systems